Southern China is not an obvious destination for digital nomads. When you think of digital nomadism, you imagine Bali, Lisbon, or Chiang Mai. Not Shenzhen, Guangzhou, or Huizhou. And yet, I spent three weeks exploring these three Chinese cities, one week in each, and it’s an experience I won’t soon forget!

This article is obviously not a tourist guide, but rather an account of what it’s really like to live and (try to) work in Southern China when you have the freedom to choose your workplace. With the struggles, the surprises, and especially that Great Firewall we’ll be talking about.

The Three Cities: Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Huizhou

I deliberately chose to explore three different cities to get a more complete view of the region. Each has its own personality.

Shenzhen (深圳) is the tech city par excellence. Bordering Hong Kong, from where I arrived, it’s China’s Silicon Valley. If you love futuristic skyscrapers and startup atmosphere, you’ll love it. It’s also the most expensive of the three, but still far from Western prices.

Huizhou (惠州) is the smallest and quietest. LessNot touristy, more authentic. To see a less staged China, it’s a good choice. However, almost no one speaks English there, and we got looks that were half-amazed to see Westerners, half-disappointed to see their country opening up to the world. A few dared to ask to be photographed with us: the hotel receptionists, and even passersby, young people, on the street.

Guangzhou (广州), formerly Canton, is my favorite. Older than Shenzhen, it has kept its soul while being a massive metropolis. The markets, old neighborhoods, Buddhist temples alongside buildings… This is where I best felt the mix between tradition and modernity. For digital nomadism, it was also the most pleasant: good value for money, numerous cafés, and a real local life.

Initially I was supposed to stay 1 month and visit an additional city, but the approach of Chinese New Year forced me to reduce my stay. This period being the largest global migration over 4 weeks, with most businesses closing to allow families to reunite, I didn’t want to either have to take overcrowded long-distance transportation, or risk not being able to eat for a few days due to lack of open restaurants. And ultimately, 3 weeks is already sufficient experience!

Administrative Formalities and Arrival in Mainland China

With a French passport, we’re one of the few countries that can benefit from a visa exemption for stays of less than 30 days: no paperwork, it definitely makes you want to explore!

I arrived via Hong Kong, on the high-speed train line that connects the city-state to Shenzhen. Like the Eurostar, Hong Kong station serves as a border zone, you pass through Hong Kong customs, then Chinese customs, in a maze of basements spanning 5 levels the size of a large city block (it’s quite different from Gare du Nord!). Nothing particular to report about passing through customs.

To continue with the Eurostar analogies, once settled in the train, 5 levels below the skyscrapers, the train continues in a 40 km tunnel, passing under a good part of Hong Kong. Much longer than our Channel Tunnel.

A few minutes before arrival, we finally exit the tunnel and arrive at a large modern Shenzhen station, which then continues on the country’s high-speed network.

Mobile Payments: Alipay and WeChat

Before entering mainland China, it’s better to be well equipped with mobile applications: Alipay and WeChat are essential, for each person.

It’s quite a surprise: it’s super easy for foreigners.

This apparently wasn’t the case before, but today: you download the app, link your international bank card (Visa, Mastercard), and it works. I did this in less than 5 minutes.

Having Alipay or WeChat Pay is the difference between living normally and struggling with every transaction.

Because in China, it’s really rare to pay with cash. Everything is paid via QR code with Alipay or WeChat Pay. Restaurants, supermarkets, taxis, vending machines, street vendors, the few beggars… really EVERYTHING.

Moreover, since transactions require being connected to the Internet, to avoid a chicken-and-egg problem, it’s better to arrive with an e-SIM to be able to pay for your first transport.

Concretely, it’s quite magical:

- many merchants have a scanner or QR code reader: you present the application in “Pay” mode, the merchant scans, 5 seconds later it’s validated.

- others are less equipped, but display their QR code: you switch Alipay to “scan” mode, scan the QR code, tell the merchant the amount to pay, and they receive a notification (often voice-only) of the amount paid.

This second method may seem completely crazy, but it’s far from rare. The downside is that you’ll have to figure out what amount to enter, as you’ll likely be told exclusively in Mandarin, with an amused look of “numbers are basic though”!

WeChat is less essential, as it will mainly be for exchanging like WhatsApp with locals. But some will be very happy to share information, photos, or messages this way.

For example, in a first restaurant, the manager absolutely wanted to photograph us and shared the photo via this messaging service. In our hotel in Huizhou, the receptionist absolutely wanted us to have a way to contact her if we got lost. And again in Huizhou, a café owner shared her location with us so we would come see her, during a conversation in a restaurant.

The app also works as a payment method, but I didn’t test it.

The experience turns out to be really smooth: you pay in foreign currency, even for ridiculous amounts of 2 Yuan, you’re immediately debited. Be careful though to have a bank card without fees so you don’t end up paying more in fees than the transaction!

Note however that identity validation will be necessary from a certain transaction amount (15000 CNY, which gives you time to see it coming).

Transportation

The metro network in Shenzhen and Guangzhou is absolutely incredible: clean, air-conditioned, frequent (a train every 3-5 minutes), and ridiculously cheap. We’re talking about 2 to 6 CNY (0.25 to 0.75€) for a trip, to be paid with Alipay. The price varies according to destination. You cross the city for less than a coffee. You receive an NFC token at the entrance which is collected at the exit: no need to buy an NFC card, nor to feel like an actor in deforestation.

I didn’t do all the lines in all the cities, but in Shenzhen some lines had “business” cars. Count on a ticket 3x more expensive (still cheaper than a single ticket in the West), but you’re then installed on a seat like in a long-distance train.

For orientation in the metro, announcements are in Mandarin and English, and all stations have names and signs clearly displayed in English. Curious oddity, before entering the metro, a security search is orchestrated, more like security theater than anything else. This is also the case at station entrances, but not at department stores as seen in other Asian countries.

Outside the metro, since no Google service is available in China (we’ll come back to this later), you can’t count on Google Maps for navigation. Apple Maps works impeccably. On Android, Amap is a local equivalent, but note that registration via a phone number is mandatory to do any search (and not all countries are supported!).

Buses are also an option, I experienced it in Huizhou. Less intuitive than the metro as not subtitled in English and drivers speaking exclusively Chinese. Nevertheless, once again, the Alipay application is incredible: no need to buy a card or ticket, you activate transport mode in Alipay, choose the city you’re in, and you get a QR code to scan when entering the bus. Depending on the bus, sometimes you’ll also need to scan it when getting off.

Small additional note, the Alipay application will generate a bus card, and for this it’s necessary to validate your identity. Think about doing it in advance as it can take about ten minutes to be validated.

It’s very smooth, as long as you know how to navigate with your phone, because nothing is translated. Apple Maps is a great help because, at least in Huizhou, the app detects which bus you’re taking and vibrates to tell you to get off.

I also walked a lot, but be careful: cities are big, very very big. Distances are nothing like what we know. We thought we were surrounded by vegetarian restaurants… yes, each more than an hour’s walk away!

Sidewalks are wide, but beware of electric scooters that ride everywhere, especially on sidewalks.

Accommodation: Affordable Hotels

We chose to stay in hotels rather than Airbnbs, as the regulations weren’t clear about the legality of Airbnbs. Laws in China are generally vague to adapt to situations, this is the case with Airbnb.

With hotels, we don’t take risks. And honestly, for the price, it was perfect.

Costs per night:

- Shenzhen: 200 CNY (28€)

- Huizhou: 210 CNY (30€)

- Guangzhou: 190 CNY (27€)

For this price, I had:

- A room with 2 double beds, clean and modern, incomparable to European standards.

- Air conditioning/heating

- Decent wifi (5-10 Mbps without VPN, less stable with)

Chinese hotels have quite a high quality standard, even in “budget” ranges like here.

Check-in requires your passport. The hotel will scan it and declare your presence to local police. This is normal, it’s the law, as in other countries in the region.

Modernity-wise, we had rooms entirely managed by home automation in Shenzhen and Huizhou: need to close the curtains? there’s a button, no need to move. No more having to get up because a light won’t turn off from the bed: there’s a button to switch to sleep mode and turn everything off at once. A spider seems to be tickling you in the middle of the night? press a button and everything lights up (on this subject, biodiversity seemed non-existent, we saw no spiders or ants)

There was even a voice assistant… if you speak Mandarin: according to the documentation, in addition to managing lights, it manages air conditioning/heating and various pre-recorded scenarios.

Even in the more dilapidated accommodation we had in Guangzhou, we’re not at all at the level of Southeast Asian standards, the equipment is identical to what you would find in old housing in Europe.

The Great Firewall: Let’s Talk Seriously

Okay, here we are. THE subject that changes absolutely everything.

The Great Firewall of China (GFW) is not a joke. It’s not “a bit restrictive” or “easily circumventable”.

Contrary to what I initially thought, it’s not designed to filter the internet, it’s designed to create the most frustrating experience possible for anything that deviates from classic web traffic, which would allow long-term access to censored resources.

What is Blocked

There are of course services that are completely blocked and completely inaccessible:

- ChatGPT, Claude Code, …

- Google (Gmail, Drive, Maps, Calendar, EVERYTHING)

- Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger

- Twitter, YouTube, Reddit

- Slack, Discord, LinkedIn

- GitHub (access very unstable and often impossible - it’s not clear, as I don’t think it’s part of the list of blocked sites, but yet it didn’t work for me)

- Most Western news sites

- And many others…

If like me your professional life depends on some of these tools, you need to think carefully before going to China.

The Solution: A VPN. Or Rather, Several.

Before arriving in China, I researched what could work, blocked solutions, uncertain ones, etc.

I read that it was particularly important to have a solution before entering China, as SSH and mosh were directly blocked by their recognizable signature. Actually not at all, these two protocols are absolutely not blocked for limited use.

However, everything we know as VPN solutions doesn’t work (especially VPNs with the biggest marketing budgets). IPSec is no, OpenVPN is filtered. I read that Wireguard should be blocked, but I had a connection to 1 of my machines that worked (while all the others didn’t establish): you really shouldn’t count on it.

From my research, what had the best chance of working was to encapsulate traffic in HTTP traffic. Because ultimately HTTP traffic is what passes most easily.

I found the wstunnel project, which worked quite well (encapsulation in websockets in HTTPS traffic), at least each time arriving in a new city it was smooth.

I also tested shadowsocks at the end, it seemed more stable to me but with lower throughput.

That said, my traffic seemed to have been spotted, so to clarify.

My Concrete Experience

-

Week 1 (Shenzhen): The tunnel worked well at first, to a machine in Paris. Some slowdowns late in the day, which intensified as the week progressed, but overall OK. Video conferences possible, emails accessible. I thought “actually, it’s manageable”.

-

Week 2 (Huizhou): Arriving at the hotel, we found great speeds again. Then it started to seriously degrade. Navigation and video conferences started to lag. I switched to a server in Singapore, thinking to reduce latency. It did improve things a bit.

-

Week 3 (Guangzhou): Hell. On arrival, as usual, it was OK, then quickly we found difficult conditions. Until the day before departure when really nothing worked properly anymore. The tunnel would disconnect every 2 minutes. Video conferences became very degraded then impossible. I spent more time trying to get my tunnel to work than working.

In short, I’d say the GFW lets a lot of things happen but learns from behaviors that deviate from what would be expected: and of course an HTTP tunnel eventually shows.

Rather than blocking, it makes the experience so frustrating and irrational (why did it still work well in the morning!!!), that you’re forced to give up. I tried changing IP, domain, software… nothing worked in the end.

That said, a solution I should have implemented earlier is to let unblocked traffic go out directly, to only use the tunnel for blocked traffic: less traffic = less chance of being spotted.

I did this by distributing a proxy.pac file generated from known filtered domains.

This seems essential to me to maintain the tunnel longer.

The Impact on Work

Let’s be clear: Southern China is really not an easy destination for remote work if your job depends on Western tools.

- Emails take time to load: I had to abandon editing an email several times

- Video conferences are random: to the point of becoming impossible at the end

- Syncing files takes hours in the afternoon and evening, some services behind CDNs manage admirably in the morning though

- Every simple task becomes a fight

After three weeks, trying to find solutions, I was exhausted. Not because of the work itself, but because of the constant friction with the GFW.

The GFW is, by far, the biggest hassle of digital nomadism in China. Everything else is manageable. But that, no.

Internet and Remote Work (Outside GFW)

Paradoxically, when you’re on non-blocked services, Internet is excellent in China.

Bandwidth is huge. 4G/5G is ultra fast. Hotel wifi is stable and high-performing for Chinese sites. If you only had to use local services, you’d be in paradise.

Cafés? Many have wifi, but it’s random: some ask for a Chinese phone number to connect. And anyway, with the GFW, it’s complicated to work efficiently in a café.

Vegetarian Food: Variable by City

Being vegetarian, it’s an aspect that’s sometimes tricky to manage while traveling.

In China, there are many vegetarian restaurants: Buddhist restaurants, neighborhood canteens serving only vegetarian dishes, but also gourmet restaurants and some vegan fast-food in tourist areas. Unfortunately the well-known HappyCow app is not very up to date, and no longer seems to take contributions into account.

A search for the term 素食 (sùshí, vegetarian restaurant) reveals gems, after bumping into several closed restaurants (either permanently, but also because they simply no longer serve: Chinese seem to eat early, and at 7pm there’s not much open anymore).

We mainly encountered 2 types of restaurants:

- buffets: which contrary to what you might imagine, even for 15 CNY, the dishes are of very good quality and very tasty. We hesitated in Shenzhen, but we shouldn’t have, in other cities we were never disappointed.

- restaurants serving sharing plates: you think you’re ordering one dish each (given the ridiculous prices, how can you imagine otherwise), and we’re served huge central plates overflowing with food, with serving chopsticks.

Chinese cuisine is incredible: very varied and flavorful. And portions are mostly too generous.

We have no trouble finding noodle or rice dishes with some large boiled vegetables always well cooked. Small anecdote: there’s no trace of Cantonese rice. I who love Vietnamese fried rice, in China it doesn’t seem to exist at all.

For a complete experience, you can easily order food via one of the dedicated mini-applications in Alipay. As elsewhere, quality is variable: we sometimes paid dearly to be served particularly greasy noodles, and other times, a very balanced and complete dish with rice for the price of a song in the West. In any case, if you meet the delivery person, they won’t believe their eyes that they’re delivering to a Westerner: bug guaranteed, with unpredictable reactions and laughter.

Meal Costs

- Simple local meal: 15-30 CNY (2-4€)

- “Gourmet” restaurant meal: 50-100 CNY (5-10€)

- Western restaurant meal: 100-150 CNY (12-18€)

Yes, you read that right. You eat for 5€ in a good restaurant, and from 2€ for a quality canteen. By gourmet, I mean attentive service in a luxurious setting, with dishes prepared with infinite care. And a billion questions: what are all these chopsticks of different sizes for? What should I do with this empty bowl and plate in front of me? Can I pour myself more tea alone? Will they hate me with all these grease stains on the table? The stress goes away when you’re presented with the bill for the grand luxury feast for less than a Big Mac menu…

SIM Card and Connectivity: eSIM, My Savior

As I mentioned earlier, I used an eSIM rather than a Chinese physical SIM card.

So I don’t know what it’s like to buy a physical card, except that it must necessarily be paid for, and therefore have a connection to use Alipay. The eSIM seems to be a wise choice.

Theoretically some “international” eSIMs route traffic outside China and bypass the GFW. In practice, I tested 3 different eSIM providers: sometimes I’d exit in Hong Kong, sometimes in China (lost!), and another time in Macau. And it didn’t help me finish my video conferences at the end of the trip, so be careful in their selection.

Electrical Outlets: Adapters and Compatibility

A question that often comes up when traveling is electrical outlets.

First, the voltage is 220V at 50Hz, which is compatible with European devices.

China mainly uses three different types of outlets:

- Type A (two parallel flat pins, like in the United States)

- Type C (two round pins, like in continental Europe)

- Type I (three flat pins in a V shape, like in Australia)

In fact, all the outlets we encountered, in hotels or public places were multi-format and accepted European plugs (Type C), American (Type A), and Chinese (Type I).

In the photo, you can see at the top the Type A and C combo, typical of Southeast Asia, and Type I below.

Language Barrier: Translation and Patience

Here’s another aspect unique to China!

Sure your interlocutors will see that you’re clearly foreigners, but never will they imagine that you don’t speak Chinese fluently like them! Anyway, very few people speak English in China.

The few young people who speak English speak it quite well, and really wanted to talk to us… to take photos with us!

In the hotels where we went, receptionists weren’t much more comfortable than the rest of the population, but are very resourceful.

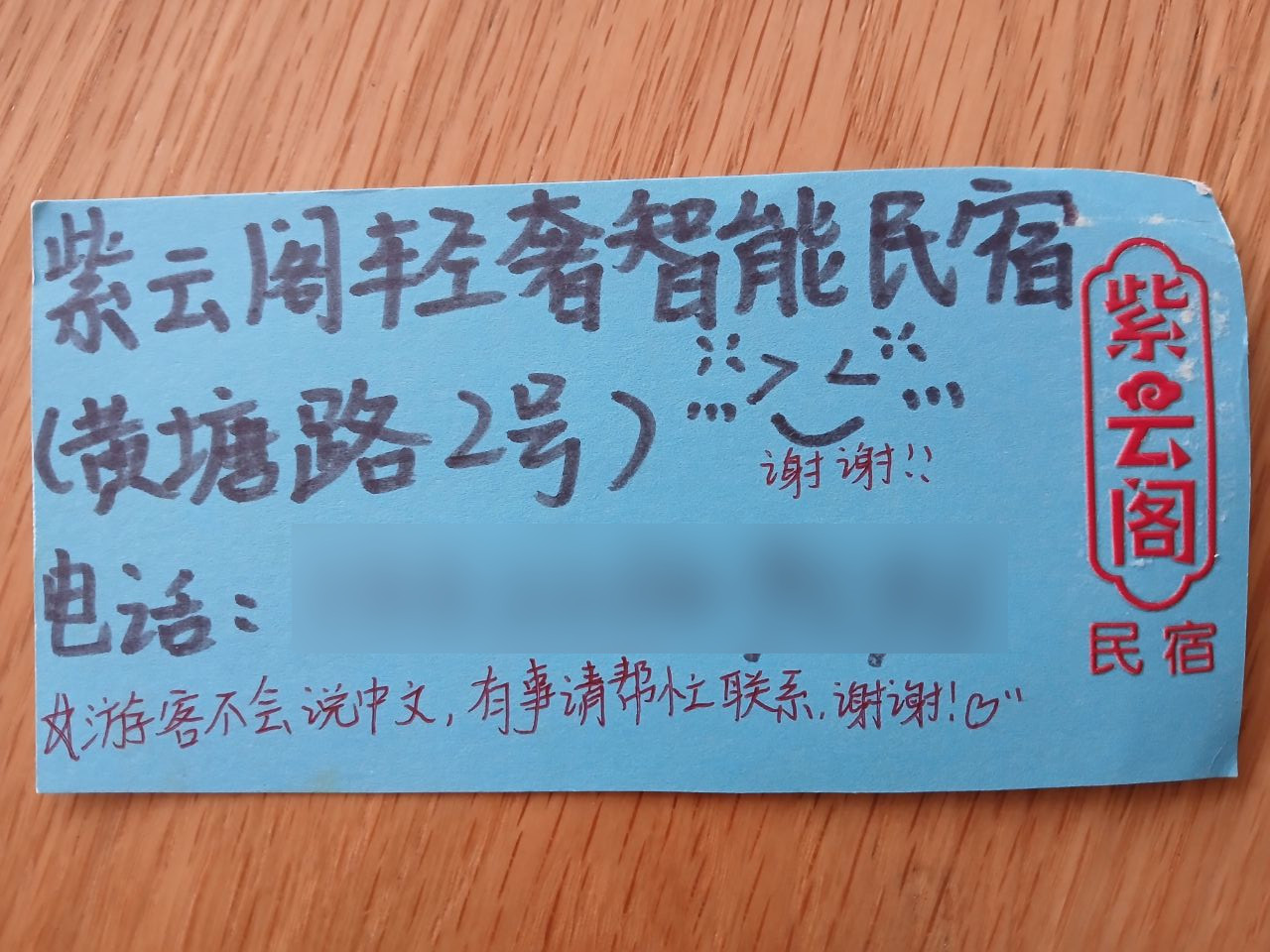

Special mention to our host in Huizhou who was afraid we’d get lost in the city and gave us a paper we should give to the first passerby we met in the street if we were lost. The concept of the paper being explained to us via a translation app:

And indeed in daily life, it’s generally expected that you adapt, using a translation app or clear miming to communicate. But they are very very patient and with a benevolent kindness rarely seen.

Learn a few basic words in Mandarin:

- 你好 (nǐ hǎo) = Hello

- 谢谢 (xiè xie) = Thank you

It shows you’re making an effort, and it completely changes the welcome.

Why Come?

Let’s be clear, China is not at all what we imagine in the West. The media, politicians, social networks sell us a monolithic, often negative, even backward vision.

On site, we discovered a fascinating country, ultra-modern AND deeply traditional. People are welcoming. Cities are clean and safe. Infrastructure is stunning (metro, mobile payments, logistics…). Food is incredible.

Yes, the GFW is frustrating. The language barrier is real. Assuredly, there are difficult and complex political aspects.

But it seems essential to me to form your own opinion about China: far from clichés. We come back with quite different thinking.

Huizhou Station

Canton Airport

Conclusion: A Memorable Experience, Not Restful

Three weeks in Southern China is intense. It’s not a relaxing beach vacation with a cocktail. It’s a total immersion, sometimes uncomfortable, often frustrating (thanks GFW), but always stimulating.

What I Loved

✅ The insane cost of living. 27€ per hotel night, 5€ for a restaurant meal, 0.50€ for a metro trip.

✅ The infrastructure of the future. Ultra-quiet high-speed trains, impeccable metro, mobile payments everywhere, top logistics.

✅ The varied and delicious cuisine. If you like to eat, you’re in paradise.

✅ The safety. You feel safe everywhere, at any time.

✅ The Chinese people: often amazed, sometimes surprised but always kind and caring.

✅ Getting off the beaten path and seeing authentic China.

What I Hated

❌ The Great Firewall, obviously. Exhausting and frustrating.

❌ The security atmosphere. It’s subtle, but it’s definitely there.

Do I Recommend It?

Yes, but rather for vacation.

If you’re aware of the challenges, if you’re technically prepared, without too heavy dependencies with the outside, and if you’re looking for an original and cheap destination, then go for it.

Southern China is for those who want a real challenge and a real adventure.

But as an adventure trip, it seems to me to be an essential country to discover.

Do I want to go back? YES, absolutely. The authenticity of the country and the Chinese people is a pleasure. It will just be necessary to adapt the stay to have fewer constraints related to the activities of a digital nomad.

Three weeks, three cities, one firewall, and lots of noodles!

Southern China is not simple. But it’s memorable.